In this series of posts, I will use data taken from the Public Security Institute (ISP)'s database to address several claims about the nature of violence and crime in Rio de Janeiro following the installation of the UPPs, including:

1. Homicide is down in Rio de Janeiro because of the UPPs

2. The UPPs have not reduced crime, so much as they have displaced it to areas without UPPs

3. Car and petty theft has been reduced since UPP installation

4. Robberies of pedestrians has gone down since UPP installation

5. Neighborhoods in the immediate vicinity of UPPs have seen a reduction in crime, while neighborhoods without UPPs have not

6. Rio de Janeiro, on the whole, is safer with the UPPs

5. Neighborhoods in the immediate vicinity of UPPs have seen a reduction in crime, while neighborhoods without UPPs have not

6. Rio de Janeiro, on the whole, is safer with the UPPs

I will address the following categories of crime:

1. Homicide

2. Other violent crime

3. Assault and robberies in collective transport vehicles

3. Robberies and "furtos" (theft where face-to-face contact with the thief was not made)

4. Threats and extortion

5. Disappearances and cadavers recovered

I have also used data on police activity in the following areas:

1. Apprehension of drugs

2. Apprehension of arms

3. Imprisonments

It should be noted that the categories are independent. For example, if a rape ended in homicide, it will be listed exlusively under the category of rape, which includes "rape followed by death." It will not appear in the "homicide" category.

In addition to the limitations to the data mentioned in yesterday's post, , there were several major changes made to the way in which crimes are categorized after 2009 (to be explained in further detail later on). It's unclear why this method0logical change was made, but it's notable that it coincides with the first year of data available in which UPPs are present. If the ulterior motive of the change in data collection periods was to make data analysis on pre-2009 crime unnecessarily time-consuming, convoluted, and less precise, the ISP has succeeded with flying colors. Now, any researcher wanting to examine the relationship between UPPs and crime must account for re-categorization and elimination of certain types of crime.

Population growth and decay has been considered, and will be highlighted when relevant.

Because the sample size is very small (data is only available for the past 10 years), a note of caution must be attached to these findings; an ideal sample size is 15 or greater.

I will begin by presenting my findings on homicide. Unless otherwise indicated, it can be assumed that any significant increases in homicide to which I refer have outpaced population growth. For example, a 4% increase in homicide does not represent an absolute increase if the population of the region in question is growing at the same rate. Population growth and decay are two factors that are usually ignored by the municipal government when it publicly discusses crime rates. For the following data presentations, it is accepted that homicide and drug trafficking in Rio de Janeiro are intrinsically linked. All data points were taken from the same months for each year to ensure consistency and accuracy.

HOMICIDE IN RIO DE JANEIRO

These are my findings on homicide in the city of Rio de Janeiro. Population growth, according to the 2010 Census, is 1.4% per annum.

HOMICIDE IN RIO DE JANEIRO

These are my findings on homicide in the city of Rio de Janeiro. Population growth, according to the 2010 Census, is 1.4% per annum.

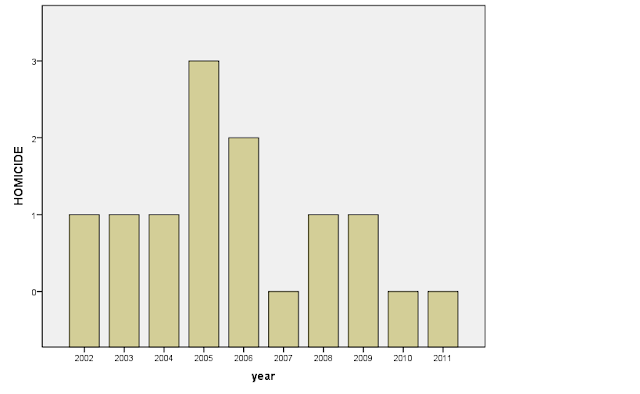

Sample Monthly Homicide Rate in Rio de Janeiro City , 2002-2011

This graph demonstrates initial difficulties in establishing causality between UPPs and homicide reduction; it would be difficult to prove that homicide incidence has been dropping due to increased UPP presence, and not because of some other independent variable.

So what is the relationship between the number of UPPs present in the city of Rio de Janeiro and homicide? I performed a simple linear regression demonstrating the correlation between the dependent variable, "homicide", and the independent variable "UPP units". While the data does indicate at statistically significant strong negative relationship (R=-.837) between the number UPP units and homicide (p<.01), the sample size, N, is too small to conclude that the decline in homicide may be related to UPP installation:

N(10)

β =-5.265, t(8) = -4.320, p<.01

A major source of concern for is the sharp increase in "disappeared persons" immediately following the installation of the UPPs in 2008. Take a look at this graph:

Sample Monthly Disappeared Persons Reports in Rio de Janeiro, 2002-2011

In general, disappeared person reports had been declining since 2002, until 2008 when the incidence spiked sharply. This pattern begs the question, if most homicides in Rio are related to drug trafficking and police intervention, have homicides really gone down? Are UPP-related occupations related to increased "disappearances"? For anyone that has seen Tropa de Elite 2, you know what I'm talking about.

Compare the pattern of post-2008 disappearances in Rio de Janeiro to those in Baixada Fluminense, a municipality without UPPs, but with many violent comunidades:

Sample Monthly Disappeared Persons Reports in the Baixada Fluminense, 2002-2011

While Rio de Janeiro's population has grown at just 1% per year, The Baixada's grew at 5%, so some increase in incidence of disappeared persons should be expected. Note that in the post-UPP period (2008 onward), there is no evidence of an overall increase in disappeared persons. Not so in the case of Rio, where these disappearences cannot be attributed to natural increase.

HOMICIDE IN GRANDE NITEROI AND THE BAIXADA FLUMINENSE

Many have postulated that, with the installation of UPPs exclusively in the city of Rio de Janeiro, traficantes have migrated east and north to the Grande Niteroi and the Baixada Fluminense, driving up homicide rates. Grande Niteroi has had a negative population growth rate, while the Baixada has grown at roughly 2% per annum.

Sample Monthly Homicide Rate in the Baixada Fluminense, 2002-20011

In this case, linear regression indicates a weak negative relationship between UPP installation and homicide incidence, that is not statistically significant (p <.01).

Data supports the claim that, in fact, UPPs may have contributed to increased homicide incidence in the Baixada Fluminense; however, it is too early to draw a conclusion. The same is not true in Grande Niteroi, where homicide has been decreasing steadily since 2002, and does not appear to have been negatively or positively affected by UPP presence. Here it must be noted that Grande Niteroi, in comparison to the Baixada, has far fewer comunidades and therefore is a less likely destination for migrating traficantes.

Data does not support the claim that homicides in the Lakes Region - a municipality in the extreme easternmost corner of Rio de Janeiro state - have risen as a result of in-migration of traficantes from Rio de Janeiro city; in fact, homicides have fallen since 2008.

HOMICIDE BY NEIGHBORHOOD

Another point of interest in homicide by region and neighborhood. Because of the micro-level analysis and relatively small, sensitive data points, I will use only graphical analysis and not include linear regressions. Unfortunately, some reporting precincts conveniently underwent a geographic reconfiguration between 2009 and 2010. Territories were assigned either more or less police departments based on their new size. These changes obfuscates research and precludes the analysis of crime in neighborhoods in which violence has reportedly gone up since the UPPs have been installed, making reports of either reduced or increased violence extremely difficult to substantiate. I have tried my best to only include neighborhoods which have not undergone these changes.

Copacabana and Leme are two geographically small neighborhoods in the wealthy South Zone. The tiny area has two UPPs, both installed in relatively small comunidades in 2009. Probably more than any other area of the city, Copacabana/Leme is praised for the successes of its UPPs. Let's take a look at how effective the UPPs have been at reducing homicide in these two neighborhoods:

Sample Monthly Homicide Rate in Copacabana/Leme 2002-2011

The UPPs in Copacabana/Leme were installed in 2009. Because the area never had a high homicide rate, it's extremely difficult to conclude that the UPPs played a role in murder reduction.

Sample Monthly Disappeared Persons Reports in Copacabana/Leme, 2002-2011

Now let's examine a neighborhood that has not one, not two, but six UPPs in its vicinity: Tijuca/Maracana/Vila Isabel. With so many UPPs (in nearly all of the area's comunidades), one would expect the homicide rate to plummet if the UPPs are having their intended affect on violent crime.

Sample Monthly Homicide Rate in Tijuca/Maracana/Vila Isabel, 2002-2011

In this neighborhood, there is no indication of an overall reduction in homicide between 2009 and 2011. The 6 UPPs were all installed in 2010, so one would expect to see a decrease in both 2010 and 2011. Instead, homicide rates for 2010 and 2011 match the overall average for 2006-2011.

Now, let's examine a neighborhood in which there are no nearby UPPs: Manguinhos/Mare/Bonsucceso:

Sample Monthly Homicide Rate in Manguinhos/Mare/Bonsucceso, 2002-2011

CONCLUSION

Overall, there is no compelling evidence to indicate that the UPPs have caused a decline in homicides in the city of Rio de Janeiro. Overall homicide rates had been declining steadily in most areas since 2002, well prior the installation of the first UPP in late 2008. More data is needed in order to demonstrate any possible causal relationship between the number of UPPs in the city and a reduction in homicides.

While initial evidence from the Baixada Fluminense - a municipality which many hypothesize has become a destination for traficantes fleeing comunidades in Rio - indicates a rise in homicides, it is also too early to tell if the increase can be attributed to the flight of crime to non-UPP areas.

The increase in disappeared persons since the installation of the UPPs is disturbing. If, for example, many of the disappeared reports represent homicides, then there could be a downward bias in the homicide rates for the post-UPP period. Hopefully, the recent spike in disappearances is not attributable to increased police presence in the comunidades (see my post on how military police cover up their involvement in homicides here).

In the next post, I will discuss incidence of other violent crimes in Rio de Janeiro in the wake of the UPPs. Following that will be a set of posts on armed robbery and other types of theft. Lastly, I will demonstrate the relationship between UPP installment and the apprehension of arms and drugs, and discuss evidence of the displacement of violence to other areas of the state.

No comments:

Post a Comment