While evidence might point to an overall reduction in homicide, the data is not as compelling for an inverse relationship between the number of UPPs in the city installations and incidence of other violent crimes in Rio de Janeiro. Once again, I have accounted for population growth and decline, and all of the possible correlations I point out I did not find to be attributable to natural growth alone. I will not perform bivariate analyses as I did in the last post after taking into consideration the limitations of the small sample size, and instead compiled the following set of visual aides and graphs.

The graph below shows the number of intentional injuries (injuries inflicted by one party on another with the intent to cause bodily harm), plotted by year, in the city of Rio de Janeiro. Remember that the first UPP was installed at the end of 2008. Four units were installed in 2009, eight in 2010, and five thus far in 2011:

Sample Monthly Intentional Injury Incidence in Rio de Janeiro City, 2002-2011

Intentional injury incidence in Rio had been relatively stable, if not on an overall decline, since 2003. There is a definite, unprecedented upswing in the number of reported intentional injuries after 2009, a pattern that is not seen in other municipalities without UPPs (such as the Baixada and Grande Niteroi):

Sample Monthly Intentional Injury Incidence in Grande Niteroi, 2002-2011

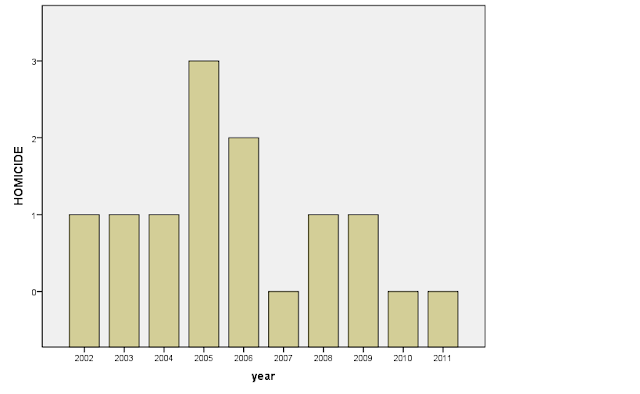

Let's examine the case of Tijuca/Vila Isabel/Maracana once more. Allow me to remind you that this is a neighborhood with not one, not two, but five different UPPs, making it an excellent area to analyze. In theory, one would expect to see a significant drop in violent crime, assuming that a) violent crime is intrinsically linked to drug gangs, and b) the UPPs are serving their intended purpose. In practice, what we see is just the opposite:

Sample Monthly Incidence of Intentional Injury in Tijuca/Vila Isabel/Maracana, 2002-2011

Note the undeniable decline in intentional injury incidence from 2003-2008. 2008-2009 marks the first increase in this type of crime since 2002-2003. Although Tijuca did not receive a UPP until 2010, the rise in intentional injuries in 2008-2009 may suggest the migration of crime; because South Zone comunidades were the first to receive UPPs, some traficantes fled to comunidades in areas without a police presence. Tijuca's comunidades are not only close to the South Zone; they also are dominated by the Comando Vermelho (CV), which off Rio's three drug factions has has been the sole target of the UPPs. As you can see in the map below, the CV (red) controls nearly all of the South Zone's major comunidades, with the notable exception of Rocinha (controlled by the Amigos dos Amigos - yellow). I have delineated the South Zone comunidades with a purple line, and those of Tijuca with a blue line. Note the proximity and shared command bf the CV of the two regions, suggesting a logical migration of traficantes explused by the South Zone UPPs. The migration of crime is another important aspect of UPP installation, which I will expand upon in greater detail in an upcoming post.

Rio de Janeiro Comunidades Mapped By Ruling Drug Faction

Another relationship that merits further examination is the relationship between disappeared persons, which I discussed in the last post, and the number of bodies found by PMs that have not yet been ruled homicides. While the number of corpses recovered by polices has plummeted, the number of persons reported missing has gone up. Incidence of corpse recovered had leveled off around 2005, after a long period of decline. Incidence dropped dramatically in 2008 after the installation of the first UPP, and continued on a declining trend, while the number of disappeared persons skyrocketed for the same time period - implying a possible correlation. While it would be easy to assume that fewer corpses found indicates a safer city, the fact that many disappeared persons are eventually ruled deceased (often by foul play), must be considered. It is quite possible that the relationship between corpses recovered and disappeared persons could indicate a) an underreporting of corpses found, b) adoption of better body disposal tactics on the part of the murderer, who now may have a 24/7 police force patrolling his comunidade, or c) an overall degradation of the quality of criminal investigations. The dual bar-line graph below is telling:

Sample Monthly Disappeared Persons vs. Corpses Recovered Incidence in Rio de Janeiro, 2002-2011

On most days of the week, the local media releases reports of what appears to be escalating violent confrontations between drug traffickers and military police (PM) in the extreme North Zone of Rio, where there are no UPPs. In particular, the comunidades of Morro da Serrinha and Morro do Juramento have become veritable battlegrounds over the course of the past several months. Existing conflict has been exacerbated by flight of CV traficantes from areas like Tijuca to comunidades deeper into the North Zone, and taking refuge in comunidades such as Serrinha and Juramento, which belong to their same drug faction and have no UPP presence. Unfortunately, it is extremely difficult to compile data on these areas, as the PM's administrative system underwent extensive revisions this year; regions were subdivided or expanded, and gained or lost police batallions accordingly. As statistics are published by administrative region after compiling data from the corresponding batallions, it is nearly impossible to compare crime data in areas affected by the border re-drawings in years prior to 2011.

Today, however, O Globo touched on a different source of violent crime in Juramento and Serrinha: tripartite conflict. No longer is the political landscape of the communidades defined by conflict between the police and the traficantes; the rise of the militia marks the introduction of a third party to Rio's urban war. Since its inception, the militia - which is comprised largely of current and ex-PMs - has further blurred the line between police and traficantes as it attempts to wrest control of the comunidades from drug lords. Militia now enjoy de facto authority in many of the city's comunidades, imposing vigilante rule on residents, extorting funds, inciting violence, and otherwise assuming a role very similar to that of the drug traffickers.

Clearly, the militia perpetrate violent crime in Rio de Janeiro. However, the extent to which the militia has contributed to increased violent crime is difficult to measure, due to its ties to the PM. Residents of areas under militia control are unlikely to confirm militia presence, much less denounce a crime that has been committed against them.

Underreporting of crime by both local police forces and afflicted residents is far more likely to occur in areas with little infrastructure and police presence, such as much of Rio's West and North Zones. Unfortunately, it is precisely these two areas that many fleeing traficantes are now calling home, and precisely these two areas where residents from razed comunidades are being relocated. Looking toward the future, it will be interesting to track violent crime related to the migration of crime and the proliferation of poverty on the city's outskirts. The result is the exact recipe for violence - an easily exploitable population and drug trafficking - that has plagued Rio de Janeiro since the CV exploded on to the scene in the 1960s.